When you look up antonyms to the word “intellectual”, you might get results such as “stupid”, “unthoughtful” and “ignorant”. I’m afraid that those words have increasingly become synonymous with “intellectual”. It’s not in my interest to disregard the intellectual sphere – a sphere that you could say I belong to and have gotten a lot of value from. However, as a part-time intellectual myself, I want to shed light on what I believe is a problem; intellectual arrogance.

I like dressing well when I’m going to my university campus. Previously I wore a tie every Friday (”Friday is Tie Day”), but now I put on a tie whenever I want to. On my way walking to the university I sometimes see construction workers, working on roads or buildings. They’re doing practical, honorable work to keep our society functioning. I’m engaged in more abstract endeavors, so encountering these people is a reminder to not take my mission as a university student for granted. These people are keeping the lights on at the university so that I can be illuminated. My formal dressing functions as a reminder that I’m not at the university to fool around. Of course, there is fun involved as well – something I have to intentionally work on since my personality is more serious – but fundamentally I’m here to get disciplined, competent, and intellectually capable. The shirt and the tie make up my working uniform. I’m not at all – and have never been – contemptuous about construction workers, let’s say, and neither do I really understand the mind of those who do. As I’m writing this, a garbage truck stopped outside, with a pair of gentlemen working to empty trash. Society is better with them, and it’s quite something to be a net-positive force. I don’t regard that occupation to be beneath what I and my peers are doing at the university. In our training period, it’s not obvious what we’re contributing, and what we’ll contribute, to society. It’s not obvious that the investment that society makes to put you at a university studying intellectual subjects will be a worthwhile investment.

Through overhearing, and engaging in, some dialogues at the university, I’ve heard the labeling of great thinkers as “old men who thought things”, multiple times. My memory may be reconstructive in this manner, but I might have heard similar sentences, but with the trio of epithets “old white men”, as if any of those group identities were important to the content that these historical figures brought forward. Aside from the apparent arrogance of such statements, it’s also frankly quite paradoxical that these historical figures are part of the reason why we even have a Faculty of Philosophy, that the students who made the statements happen to belong to. What’s a voice like that trying to convey? Do they think you can go down to history by simply thinking things? Do they think that these people were stupid? Do they think that they know better? And even if we nowadays might know more about how the world actually works, you have to take the historical aspect into account: Of course, they didn’t have the scientific knowledge and technological advancements that we have today. These people were still smart and wise, and that’s why they’re in the course literature. We don’t get to stand with the benefit of hindsight and discredit these people. Perhaps the most pronounced example of this act, in the domain of psychology, is against the great Sigmund Freud. Yes, a lot of his theories are unscientific and today discarded, but don’t forget to mention that the concept of the unconscious, the technique of psychoanalysis, and other ideas from him, are now mainstream psychology. It’s either ignorant or disingenuous to only highlight what someone got wrong, while not acknowledging what they got right. I hope this is a small minority case, but some modern intellectuals put themselves on a pedestal that’s both high in the societal hierarchy, but also above eminent figures in their own domain of expertise.

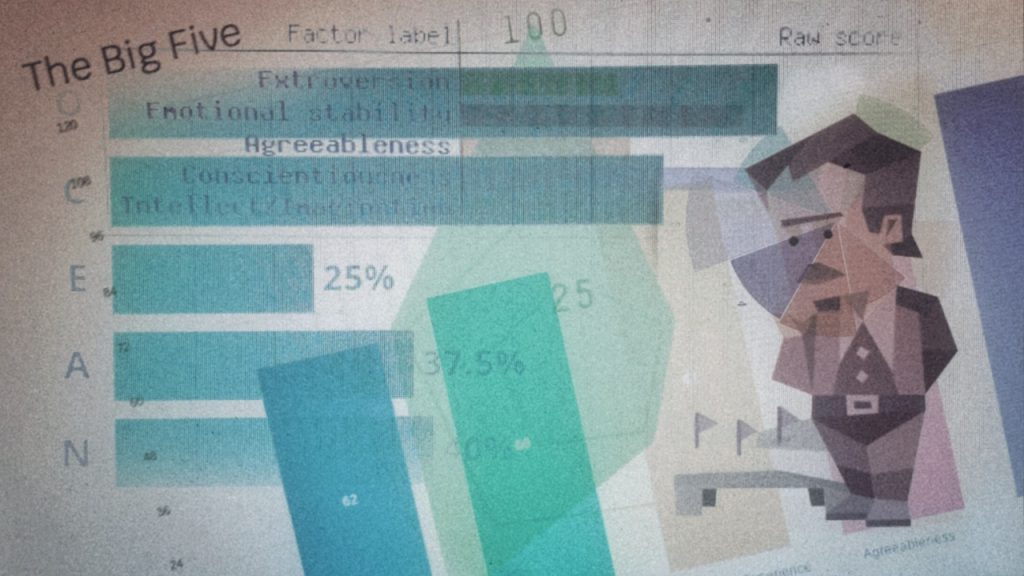

Along with arrogance about the supposed superiority of academic endeavors, I’ve also detected a lack of intellectual curiosity to be a problem among some intellectuals. I react very strongly to lazy attitudes with regard to these studies – in myself and others – especially when a disinterest in these subjects is expressed. The idea that the humanities aren’t interesting just baffles me. You’re studying psychology and philosophy for God’s sake! It’s the exploration of the universe that is the human mind. If you’re not interested in that, you’re either low in the fundamental personality trait “openness to experience” (in which case you’d probably not choose to study these more abstract and theoretical subjects) or you’re simply not paying attention. Sure, I’ve taken classes in statistics and logic that didn’t fully captivate my intellectual mind, and there was a lecture about modern liberal ideas that didn’t have the scientific validity or historical significance as ideas in most other lectures, but generally speaking, I believe that diving deep into an intellectual topic or a historical person could be the gateway to a long gripping journey. There will always be things to discover and learn, as this universe of the human mind will never be fully exploited. Reducing the study of this vast universe to the aspects that will be required to pass a course doesn’t do it justice.

I’m not saying that I’ve got my life together more than anyone else in my league. When I’m writing, I’m straightening out my thinking on problems and solutions that I myself can learn from. The advice I give also applies to me. So if you’re a university student or a student in general for that matter, I suggest thinking about how big of a role writing tests and getting grades are in your academic journey. Attending higher education is so much more than getting through the cycle of trying to identify what will be on the test, cramming nights before the exam, and then partying away to celebrate the knowledge that you lent for a few days. I recently got two unexpectedly good marks. I did perform well at these examinations, but I’m more concerned about what I learned, so when there’s a distance between the grade I get and my estimated knowledge about the subject, I can feel a disconnection from the educational system. I’ve experienced that the threshold for passing is too easy to exceed, leaving it up to me to properly challenge myself. Rarely have we in class been tasked with exercises that require a lot of thinking, which is partly why I’m writing and publishing these texts. I’m not contemptuous about any of this – at least not consciously and at least not to the degree that I could – but I’m stunned by the lack of thinking a student is required to make in order to study subjects that are fundamentally about thinking. If we’re not engaging in thinking, how can we take pride in belonging to an academic association?

Of course, this contempt can be mutual, where non-intellectuals may despise intellectuals. I think that I understand this critique better; I feel like it’s mostly a matter of intellectuals kicking “down” and non-intellectuals responding, to the degree that it’s happening. However, I don’t believe that the perspective of despising intellectuals is productive either. To bridge this conflict, I would suggest meditating on the usefulness of both the academic, and non-academic way of being. We need each other: We need academics to do the intellectually demanding job of being the keeper of the flame of intellectual traditions that beautifies and enlightens the world, and we need non-intellectuals to do the physically burdensome work of maintaining the very societal functions that allow for these intellectual endeavors, among other crucial components of society. But most importantly, we need people to bring their best to the table, whether that’s working with our infrastructure or culture. Because you can do a hell of a job – in both senses of the expression – on both these fronts. We’re all human beings, and we all have the capacity to bring about good and evil. So maybe we should focus on deciding what we want to create, and set aside our trivial differences in achieving it.